Architects and designers engage regularly in the topic of leisure and free time: often solicited by design companies, they try not only to project objects dedicated to games, sports, outdoor spaces and comfort; if you think about it, even the first household appliances, born as avant-garde design objects, were made to save time for other activities. One of the most spectacular editions of the Triennale di Milano of all time, the 13th of 1964, was based on the theme of free time: it is no coincidence that this phenomenon was beginning to affect culture in the '60s, in the midst of the economic boom and the spread of mass production, with consequent repercussions on society and design.

The Italian section of the exhibition, coordinated by Umberto Eco and Vittorio Gregotti, was structured on a series of spectacular displays, which triggered deep reflections on the theme of free time: is it not conditioning itself to deal with how to organize our freedom? Are prefabricated holidays buildings nothing else than an alteration of the natural landscape? Or what about TV (the exhibition displayed the 'Cynius' model by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni for Brionvega), an object born for fun and entertainment: is it not above all just a box spreading advertising messages?

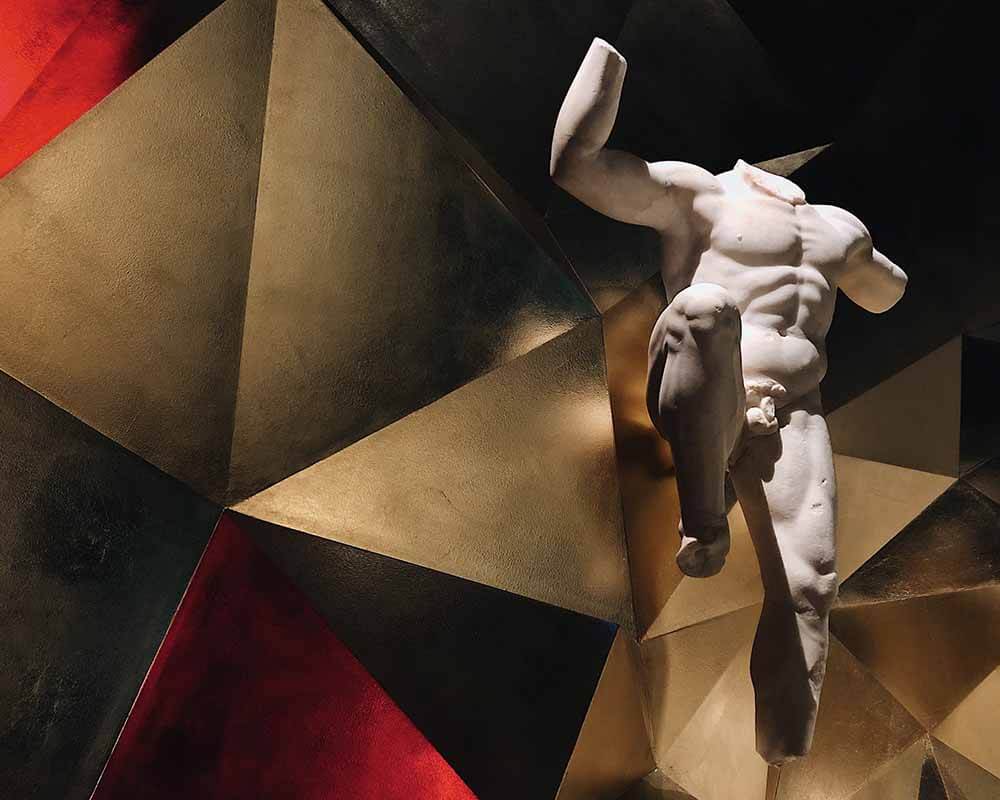

Among the most spectacular displays in the show was the mirrored labyrinth by Nanda Vigo, Lucio Fontana and Enrico Baj, which invited visitors to lose themselves, to be disoriented, to reflect first of all on what leisure time is not, as well as on the intrinsic concept of freedom. The show then encompassed sections from different countries in the world: stories made of images, works by great artists and objects designed by famous designers dealing with the world of hobbies, travel, entertainment and sports. Among some of the best examples of made in Italy design stood out the very thin 'Fourline' upholstered armchair by Arflex, designed by Marco Zanuso, the rattan armchairs by Bonacina, the garden furniture such as a sculptural bench by Roberto Mango, the beer dispenser system by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni for Poretti; there were also many objects made of plastic, the most innovative material of the '60s, such as the children chairs designed by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper for Kartell.

It is curious to note how certain trends presented by an exhibition dating back more than fifty years ago, draw parallels with contemporary taste and needs: for example, the necessity to combine high quality with lightness in furniture, or the spreading of multitasking furnishings, adaptable to small spaces. Joe Colombo for example, dedicated to food, a beloved hobby of our times, a curious and compact kitchen cabinet designed for Boffi. In a parallelepiped on wheels measuring just 75x75x90cm, there was everything the most demanding chefs would need: from oven and stove to a cutting board that served as the lid of a refrigerator; naturally, there was no shortage of compartments and small drawers for cutlery, plates and glasses.

.png)