photo: Giovanni Signorini, "I fuochi d'artificio sul Ponte alla Carraia per la festa di San Giovanni" (1843)

Preparations are in full swing in Florence for the feast of St John the Baptist, the city's patron saint. The celebrations will be even more special because they come after two years of forced stop due to Covid, two years of uncertainty during which the celebrations were reduced to ensure respect for the rules. This year, the celebrations will finally return in the streets of the city, and they will consist of several moments: the initial Procession of the Deputation with the Historical Procession of the Florentine Republic to deliver the Cross of St. John to the Mayor of Florence, the exhibition of the Ceri, the Historical Procession of the Florentine Republic with the characters in historical costumes, the final match of the Florentine Historical Football, the il Palio remiero, and finally culminating with the famous Fochi, the fireworks show that will light up the sky above Florence.

The feast of St. John has ancient origins, both in religious celebrations such as the exhibition of the Ceri, and in more popular ones such as the Calcio Storico. Starting in the 14th century, nobles and lords celebrated the city's patron saint by donating large candles ("ceri" in italian) or votive offerings to churches, which were essential for lighting the interiors of churches in an era without electricity. As the centuries went by, the prestige of the city and the noble families grew and the candles became larger, more decorated and more precious. Some were made especially for the Baptistery of San Giovanni, others to be sold to fellow citizens and tourists who have always come from all over the world to take part in the celebration.

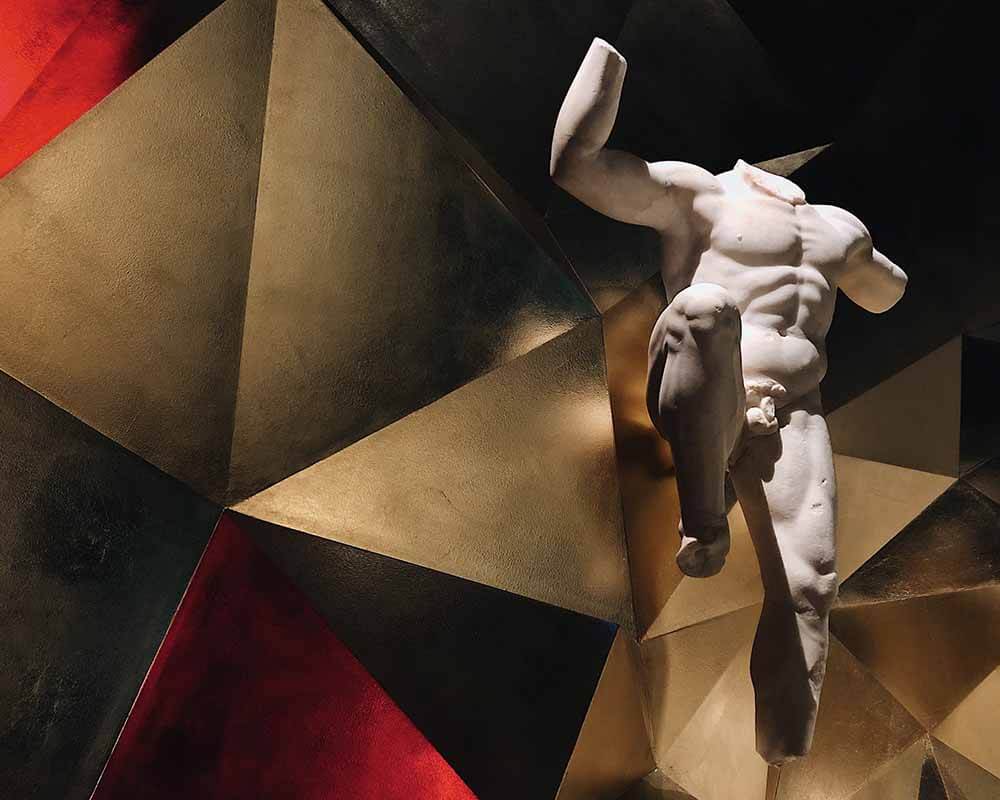

Calcio Storico Fiorentino also has ancient origins: historical sources attest to its existence since Roman times, but the most famous match that inspired the re-enactment is certainly that of 17 February 1530, when the Florentines besieged by the troops of Charles V showed their confidence and carelessness by organising a match in Piazza Santa Croce. From the end of the 17th century, the sport was gradually abandoned, only to make a comeback during the last century. Compared to contemporary sports, Calcio Storico Fiorentino can be considered a mix of wrestling, rugby and football. In medieval times, this game was mainly played by rich aristocrats (including some future popes). Today, it combines the charm of a historical re-enactment with the adrenalin rush that only a real match (or, indeed, battle) can give. Calcio Storico is in fact rather raw and at times almost brutal, but much loved by the inhabitants of the four historical Florentine quarters, namely the Blue, the Green, the Red and the White (respectively of Santa Croce, San Giovanni, Santa Maria Novella and Santo Spirito).

This fighting spirit goes well with the choice of the patron saint, St. John the Baptist, the saint of strength, courage and rectitude, who has been the patron saint of Florence since the 6th century during Lombard reign. It was Queen Theodolinda who chose him as protector of her people and the cities subject to her rule, having the Baptistery dedicated to him, or 'Il mio bel San Giovanni' ('My beautiful Saint John') as Dante calls it in the nineteenth canto of the Inferno, built on the remains of an ancient Roman villa. Before Saint John the Baptist, the patron saint of Florence was the god Mars, the pagan god of war who represented Florence's pride and fighting spirit and who was replaced with the transition to the Catholic rite.

The feast of St John the Baptist in fact combines traditions and symbolism borrowed from paganism with others of a Catholic nature. This is the case, for example, of the Fochi, the spectacular final moment of the day dedicated to the saint, which take up the ancient tradition of lighting bonfires around the city and the countryside to drive away evil spirits on 24 June, in the summer solstice period. Maintaining the date and celebrations, the Catholic tradition introduced the figure of Saint John the Baptist as a model of rectitude and strength, thus maintaining the ancient tradition that sees the feast as a moment of victory of light over darkness.

.png)