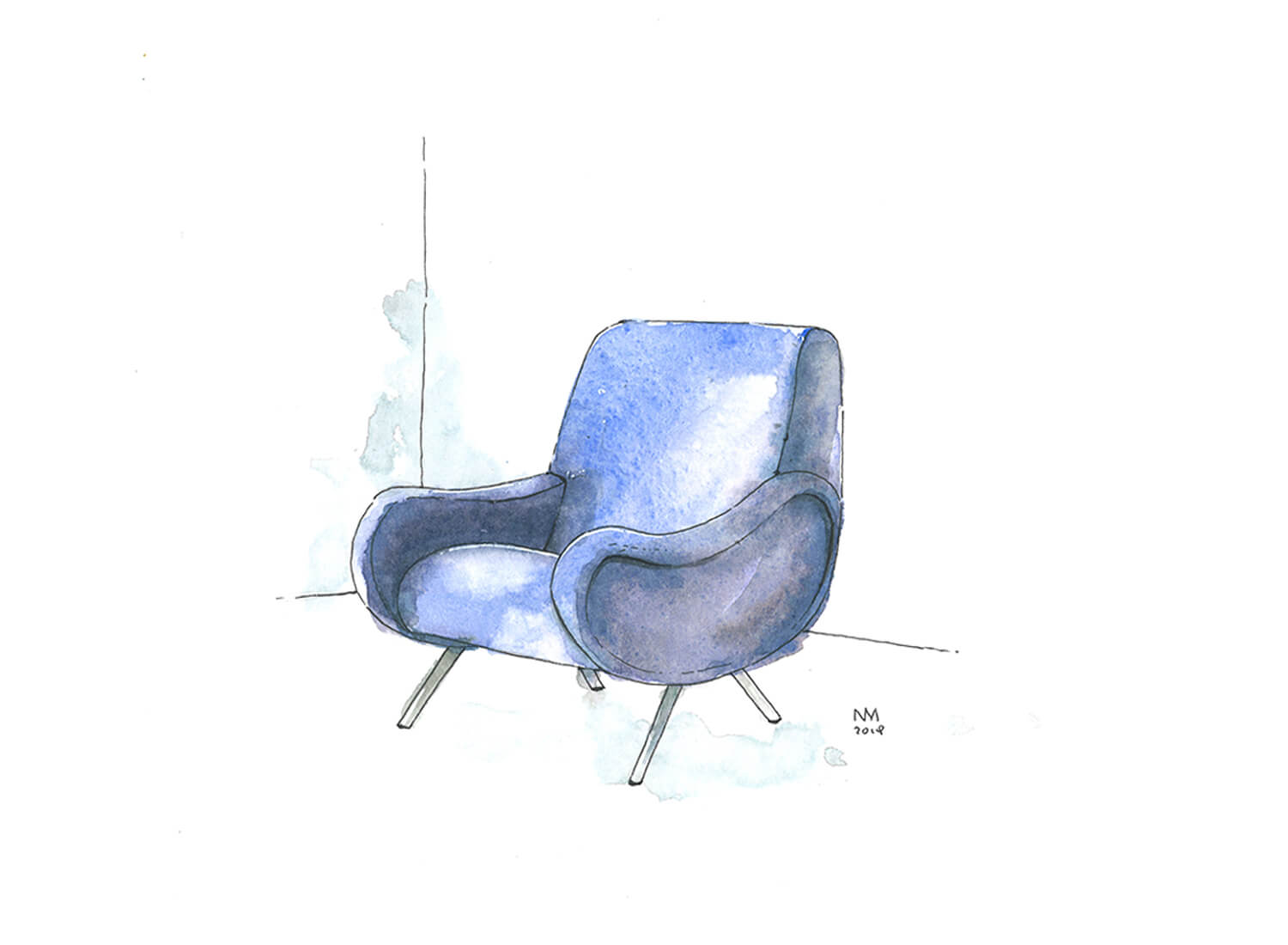

In every indoor (often also outdoor) environment we find at least one. Sometimes to stand alone, sometimes we use it in pairs or even several people. We know the position to have on it from the very first months of our lives and we use it naturally in our everyday life. It is the chair. What, however, really defines this object? It seems obvious, but it is not. How many times have we tried different chairs in furniture stores and found them too high, too low, unstable, uncomfortable...? Is it comfort, ergonomics and, therefore, function that define the chair object or is there room for interpretation in its intrinsic concept? Throughout the history of art and design, many have asked themselves these questions, let's discover together how the subject has been addressed in the last century.

In 1944, Bruno Munari (Milan, 1907-1998) questioned the design method of many colleagues, criticising the forced need to seek novelty and originality every time in the object they were going to create, often to the detriment of what should be one of the fundamentals of the object itself: comfort and practicality. With the irony that has always distinguished him, he takes up the "armchair" case, which is the most obvious, and publishes a provocation in Domus magazine: One comes home tired from working all day and finds an uncomfortable armchair. You understand that one can go on for a thousand years (and perhaps even longer) inventing ever different pieces of furniture, following all the fashions of all countries, the materials that industries throw on the market every moment, the trends, etc., all to satisfy the taste of the good bourgeois who does not want to have an armchair in his home that is the same as the one his office colleague has. (...) We will be able to say that we have worked for us, for Man (and Woman) and not just for Flair (or Bizarre). (...) Tell the truth: would you also buy an armchair where you are sure you can rest, even if everyone has this model?

A year after this publication, the designer presented the Chair for Very Short Visits for Zanotta. Created in only nine examples, its most evident peculiarity is the seat, inclined at 45° to suggest the guest not to stop too long. The materials are the classic ones we could attribute to the chair archetype: wax-polished walnut wood with inlays and an anodised aluminium seat, perhaps to ensure a better glide of the guest towards the exit. The product proposed by Munari doesn't deny the essence of the object, but questions its comfort and ergonomics. Can we call it a design object? Perhaps even a game or even a work of art. An ironic provocation? Perhaps all together, Munari's chair is intelligence, it is fun, it is art.

Leaving the world of design, we find similar questions in Conceptual Art: introducing us to this current is Joseph Kosuth (Toledo, 1945) in 1965 with One and Three Chairs, a work consisting of a chair, a photograph of the chair and a large-scale printed reproduction of the entry 'chair' from a dictionary. The meaning of this artistic intention is clear: to make us meditate on the relationship and reciprocal value of words of images in relation to what we call 'reality'. Its intention is very strong: to neutralise any question of aesthetic pleasure in the most radical way, by eliminating it. The concept says, logically and semiotically, all that is necessary to enjoy the work.

In 1974, Alessandro Mendini (Milan, 1931-2019) was editor of the magazine Casabella and for the cover he decided to enact a significant denunciation performance by literally setting fire to his Lassù, a work with an already very critical tone since it consists of a chair created to be unattainable and, consequently, unusable. An object totally devoid of functionality elevated to a work of art with a mysterious and primitive language. With the gesture of burning (and so completely destroying) the object, the designer wants to further emphasise its lack of practical relevance as well as its limited lifespan; even objects are born, die and have their own dramatic existence. Once again we are asked the question: is it function that determines an object such as an ordinary chair?

Looking in modern pop culture we can find other critical references to the importance of the functionality of objects: an example can be found in the 1997 film Men In Black directed by Barry Sonnenfeld. Here we see a subtle ironic critique of the actual practicality of one of the most recognisable design objects of the second half of the 20th century: Henrik Thor-Larsen's 1968 Ovalia Egg Chair. In one scene of the film, in fact, the main character (Will Smith), along with others sitting on the egg armchair, is subjected to an exam to test his intellectual abilities in order to join the special MIB section.

We immediately notice the group's difficulty in sitting on the armchairs which are obviously not suitable for the simple action of filling in the sheets of paper handed out. The protagonist is the only one who thinks of bringing a small table closer to him so that he can lean on it and write more comfortably. This simple gesture not only shows us the character's predisposition to the famous lateral thinking, but also makes us reflect on the concept of the ergonomics of a piece of furniture, in this case an armchair, in relation to the context.

The Ovalia Egg Chair, like the better known Egg Chair by Eero Aarnio, is certainly representative of the Space Age style of the time in its form and the materials used, but extremely limited in its practicality: it can essentially be used to relax, of course, but it is not suitable as a seat in the broadest sense of the term or to facilitate social and relational exchanges given in fact its enveloping and insulating form.

Jumping forward to the 21st century, we land at the 2016 edition of the Salone del Mobile, when Nendo proposed a collection of 50 chairs he designed inspired by the world of Manga comics. Manga is a genre of graphic illustration deeply rooted in Japanese culture and its origins can be traced back to Ukiyoe prints, developed between 1603 and 1868 AD. It represents a medium of expression with a high degree of flatness and abstraction, composed of a series of lines. The 50 Manga Chairs created by the designer for Friedman Benda therefore consists of 50 seats aligned in a grid, each evoking a sense of history and each featuring a design element taken from the manga world. For example, a 'comic strip' or 'effect line' are added to visualise a sound or action; or emotional symbols from manga, such as 'sweat' or 'tears', are formed so that a sense of story and character can be felt. Not everything is taken from manga, however: rather than making coloured or textured objects faithfully inspired by Japanese comics, the designer opts for a more conceptual solution with the mirror finish, which can generate new spatial dimensions in reflecting reality. We are faced with an extreme in the representation of the chair object: function is not contemplated at all, only some of the recognisable features of the furniture are retained, but a language totally opposed to practical and physical reality is chosen, referring to the two-dimensional and graphic sphere of the comic strip.

.png)