In an era in which the idea of recycling, reuse and upcycling are increasingly present themes — and particularly dear to us at intOndo as fans of vintage furniture! —, one almost forgets that, already in antiquity, the concept of reuse of materials, especially marble and bronze, was a common attitude, bringing with it critical issues and contradictions

For centuries, in the ancient world, statues and architectural elements composed of precious materials, such as marble and bronze, were regularly and intentionally reduced to dust in order to obtain new building material for chirches, bridges, weapons and different kind of tools; and in parallel, many works of art and architecture were instead reworked, modified, acquiring totally new functions and purposes through different eras. Furthermore, in the wake of misunderstandings and involuntary errors, an ancient capital could be transformed into a stoup, and a latrine from the Roman Empre would end up being a papal throne in the Middle Ages!

Among the most emblematic examples is the Cathedral of Syracuse (in the photo), which rises in the heart of Ortigia with its elegant Baroque facade and polychrome marble floor: explore it, and you will discover that its structure incorporates, very well preserved, the Doric columns of the imposing temple of Athena, one of the most famous Greek temples in Doric style located in Sicily, dating back to 480 BC. In the 6th century AD, a Byzantine church partially saved the temple by superimposing the original structure and transforming it into a church with three naves, with solid walls raised in the space between the columns. Probably used as a mosque during the Arab domination of the 9th century, the building returned to host Christian worship as a Norman church in the 12th century, when a new façade was built and the central nave raised, in order to open windows to make the interior brighter.

The phenomenon of reuse over the centuries has meant that, on the one hand, extraordinary works have been able to be preserved, often by changing their intended use, and on the other, due to practical, ideological or merely survival reasons, a large number of works have been destroyed to obtain raw materials. Today this would be inconceivable, but in the ancient world, the modern concepts of protection and preservation of cultural heritage had yet to emerge and develop.

Generally, the history of art attributes to Raphael (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), the role of the first superintendent in history; in a historical moment in which the practice of reusing fragments of ancient buildings was the order of the day, Raphael intended to put an end to the reuse of Roman material which was reused as building material. Making use of experts, Raphael was the first to carry out a mapping of the monuments of Rome — in particular when he was commissioned to search for marble for the construction site of St. Peter's basilica — in order to prohibit the destruction of relevant materials, epigraphs and ancient fragments found in the city area, preventing them from being destroyed or reused as building material.

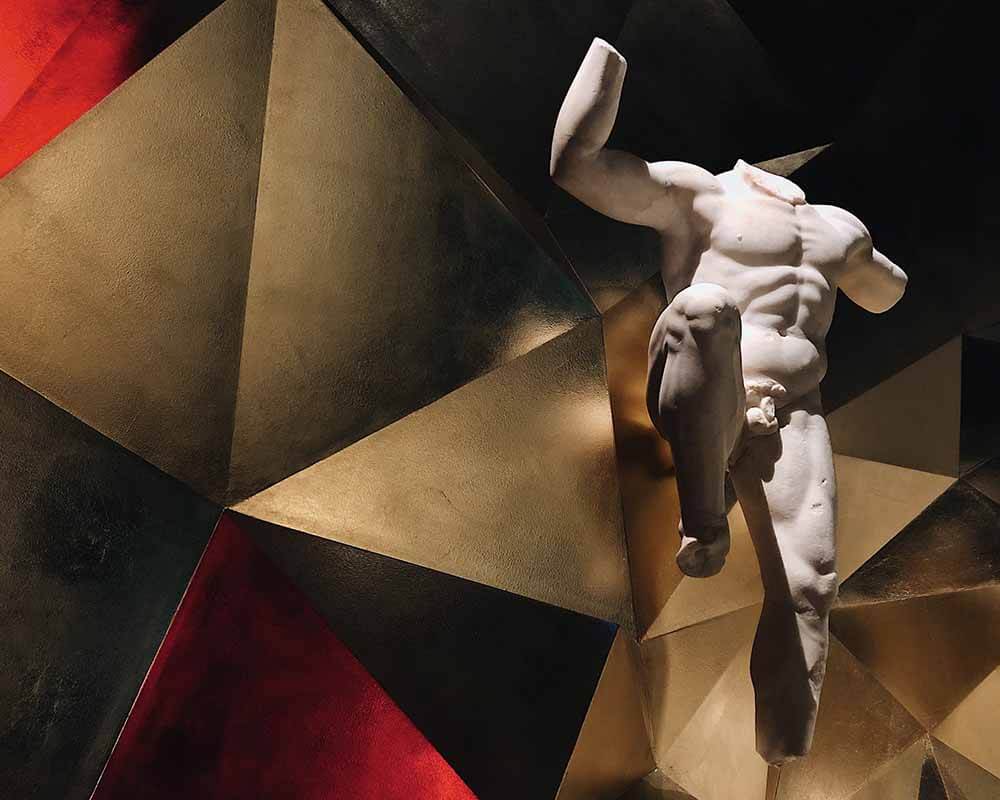

The reflection on the value of the reuse of materials in history is automatically a very interesting reflection on the contemporaneity of ancient art, on its "de-dramatization": from its state of sacredness, purity and uniqueness to a state of continuity. A work can be forgotten for millennia, buried, to then resurface in the present time with a new face, encompassing multiple meanings. The recent "Recycling Beauty" exhibition developed around this theme, staged last September at the Prada Foundation in Milan, was a show that proposed a profound reflection on the theme of reuse, gathering from Italian and international public collections a scenographic overview of classical finds: statues, busts, urns, marble slabs, friezes, sarcophagi and decorative elements, all united by the fact that they underwent displacements, modifications and took on different uses over the centuries.

To name a few, among these was the Minerva Orsay statue. Apparently intact, it is actually a suggestive mix: her torso dates back to the empire of Hadrian, while the bronze head, hands and feet are an addition from the 17th c., then replaced in the 18th c. by marble elements. Also on display was a monumental 11-metre high sculpture of the Colossus of Constantine, (once standing in the Basilica of Maxentius), which was actually a contemporary reconstruction made from research of its original found elements. The very fact of being protagonists of an exhibition in 2022 has given new visibility, faces and meanings to each of these works, in an extraordinary time journey spanning from antiquity through the Baroque and reaching the modern age with great impact.

.png)