Astonishment, wonder and curiosity were what the owners of these original furniture wanted to arouse in their guests when they opened their doors. Treasures from all over the world were hidden in the splendid cabinets of the mansions of explorers and noblemen who wanted to demonstrate their knowledge of the world.

In the beginning, the use of these cabinets originated during the Renaissance and Baroque periods and was mainly related to the collecting of relics belonging to the religious sphere. These objects were often made of precious materials and, consequently, had a considerable economic value.

At the end of the 15th century, however, after the discovery of America, western European civilisation realised that something had drastically changed in the perception of the earthly spaces and their boundaries: the world hid new lands to be discovered and conquered with countless treasures to be brought home. Thus manifested was man's innate desire to know, study and organise the reality of a world that was constantly expanding its horizons. All fuelled by the desire to get rich.

Ships laden with expectation ploughed the oceans in search of fortune in foreign lands, only to return to Europe with holds full of riches and... original objects.

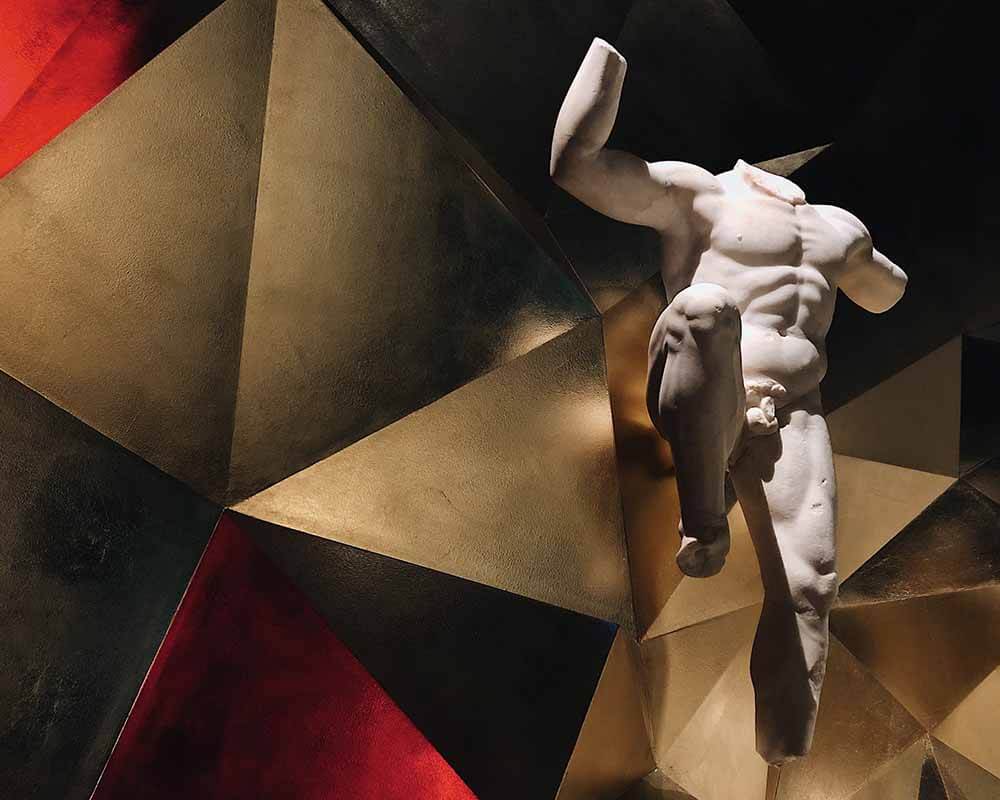

This then became the cult of man in the 16th century: wonder, the possession of that which aroused such a sensation was synonymous with a domination of the world that was complex to contest, since the true role of science in explaining reality was not yet clear. Everything that was brought back from voyages of exploration was perceived as exotic, bewitching and strange, almost magical; unknown artefacts and natural elements were enclosed within glass cabinets, sideboards and cupboards (sometimes entire rooms specifically dedicated to them) that noble families displayed in their homes to visitors. A gesture to show off the novelties of the New World, but above all a power strategy to highlight their knowledge and, above all, wealth in the eyes of their guests.

In 1565, Samuel Van Quiccheberg wrote what was considered to be the first real guide to collecting, preserving and exhibiting: the text was based on his experience as scientific and artistic advisor to the Duke of Bavaria, whose cabinets of wonders he had helped to create. According to the author, the contents of these cabinets could be categorised into different categories: artificialia, antiquities and man-made works of art; naturalia, plants, animals and other objects of nature; scientifica, scientific instruments; exotica, objects from distant lands; and mirabilia, a generic term for all objects that aroused wonder.

This gave rise to a totally new form of collecting compared to the medieval form of collecting relics: collected from every corner of the globe, these objects represented what Quiccheberg called the 'theatre of the world'. Often the only thing that united the objects crammed onto a shelf was their rarity.

Soon, the mirabilia collected within these furnishings became so numerous that the need arose to transform a single cupboard into real exhibition rooms: known as Wunderkammer, chambers of wonders, their purpose was to reproduce the world in an encyclopaedic manner. Artefacts were used to represent the four seasons, the months of the year, the continents or even the relationship between man and God. In the Wunderkammer, science, philosophy, theology and popular imagination worked together harmoniously to animate the collector's world view. The recreation of the world thus offered a unique opportunity to take control over a seemingly meaningless existence in a chaotic cosmos.

At the end of the 17th century, however, this trend began to undergo a crisis at a time when science had progressed so far that it became impossible for humans to blindly believe in the fanciful origins of collected objects. It reached the point where it was indeed difficult to believe that one was dealing with a dragon tooth and not a shark tooth. The objects that until a few decades before held a predominant role in the chamber of wonders slowly lost their power to arouse that precious feeling of wonder.

In the 18th century, chambers of wonder were going out of fashion, while museums were coming into their own. Some of Europe's most famous museum collections set up in dedicated structures as we know them today, in fact, were founded from the collections of private individuals and in time were opened to the public, giving rise to the contemporary idea of the museum.

.png)