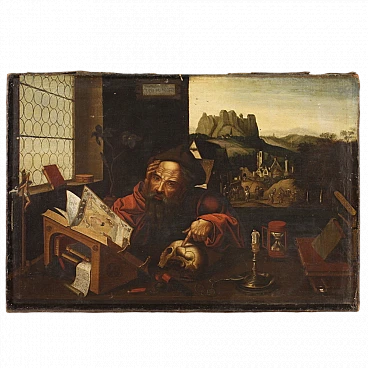

Giuseppe Marullo (Orta di Atella, c. 1610 - Naples, 1685), Suicide of Lucretia, oil on canvas, 132 x 94 cm, framed 148 x 110 cm. Published in Achille della Ragione, Scritti di storia dell'arte, Edizioni Napoli Arte, Naples, May 2014, p. 69. The painting depicts Lucretia plunging her dagger under her bare breast. Lucretia was a Roman matron, made famous mainly through the accounts of Titus Livius, who narrates how she was first threatened and then abused by Sextus Tarquinius, an event that led to her taking her own life. In the three-quarter pose, in the face contrite with pain, as well as in the softness of the chiaroscuro passages, albeit rather contrasted, one recognises pictorial peculiarities typical of the Neapolitan cultural climate. Indeed, there is no lack of references to Andrea Vaccaro - one can see the Cleopatra in the Prado Museum, Madrid and Lucrezia in the Private Collection - as well as to Massimo Stanzione. It is indeed in the latter's vein that the author of the painting in question can be traced, and in particular his companion and pupil Giuseppe Marullo. It is the biographer De Dominici who provides us with the little information that has come down to us about Marullo and who includes him among Stanzione's pupils and in a prominent position; in fact, on the master's death, it was Marullo himself who received the master's spiritual testament, his collection of drawings of 17th-century Neapolitan painters and a great deal of biographical information about them. De Dominici gave him as a native of Orta di Atella, without specifying when, and died in Naples in 1685: it is possible to establish his birth in the first decade of the 17th century, his first certain work being an altarpiece signed in 1631 in the Church of the Pentite in Castrovillari, Calabria. Making up for a lack of written documents is Marullo's habit of signing, often in Latin, and dating his works, so that it has been possible to restore - but only in recent times and often thanks to restoration work on the paintings - the painter's works and to know his evolutionary path. In fact, for a long time Marullo was a personality little investigated and recognised by critics, and this has often led to his works being confused with those of his master, as happened with a Saint Agatha passed off as a work by Stanzione, but actually referable to Marullo's brush. The Saint Agatha, moreover, shows similarities with the Cleopatra in the Hoyos collection in Rosenburg, Austria, returned to Marullo by Schultz. For a long time considered by critics to be an imitator of the mannerisms of the St. Agatha painters but also of Pacecco de Rosa, a painter who in fact inspired him for a certain period, Marullo's closer inspection reveals instead an autonomous personality capable of fusing and revisiting the languages of Neapolitan painting around the middle of the 17th century. While he was alive, his activity certainly enjoyed a good reputation, as demonstrated by the presence of numerous of his paintings in the inventories of the most important Neapolitan families of the time, as well as a number of public commissions, which have unfortunately disappeared today, such as the cycle executed in 1644, both on canvas and in fresco, which Marullo completed in the cupola and presbytery area of the Church of San Sebastiano. In 1646, on the other hand, payment was recorded for the completion of the canvases for the ceiling of the Pietà dei Turchini.The artist's production, which was quite prolific, mostly consisted of works of a religious character and destined for Neapolitan and provincial churches, although there was no lack of allegorical and historical themes, of which this one is an example, and which demonstrates the painter's attention to subjects in vogue at the time. He also executed several paintings for Domenico Mazzarotta between 1643 and 1644, including three untraced portraits. De Dominici reports that he received a commission from the Spanish ambassador Pedro Antonio de Aragon for twelve paintings, which he completed in Naples, where the ambassador moved from Rome in 1666 to hold the office of viceroy. Among the works in the museum is The Miraculous Peach, in the picture gallery of the Campania Museum in Capua, signed 'Joseph Marullus' and considered by critics to be one of the artist's best works for the perfect fusion of cultural elements derived from Stanzione's examples, and effective luministic solutions perhaps derived from Stomer. In Achille della ragione, Giuseppe Marullo Opera Completa, Edizioni Napoli Arte, Naples, 2006, a detailed survey of the artist and his works was conducted, to which the author himself returns in the essay Una scoperta e una riscoperta per Marullo, published in Achille della Ragione, Scritti di Storia dell'Arte, Edizioni Napoli arte, Naples, May 2014, p. 69.

SILVER Seller in Milano, Italia

SILVER Seller in Milano, Italia

.png)