Originally from Berlin, where he trained as a woodcarver, Peter Schade has been working almost exclusively with antique picture frames since he came to London in 1990. Today he is among the experts in antique frames and one of the few who combine a profound knowledge of his subject with the ability to master the art of frame making. His sensibility for displaying painting brings him around the world in search of these understated collectible objects. Let’s learn more about his past and present work.

1. Florentine Palazzo Pitti frame, 16th century

I was 16 when further academic education was not possible for me in East Germany and I had to look at possible apprenticeships. I come from a family of artists and art historians and thought that woodcarving looked interesting. After my apprenticeship, I worked for several years for a building conservation company in Berlin. When the Berlin wall came down I had the opportunity to go to England and found work with Arnold Wiggins and Sons, one of the great international frame dealers and makers in London. I worked there for three years and started my own business in 1993. This is a very grand Florentine Palazzo Pitti frame, which I bought it at a Christie’s sale when I was 27. I knew of the frame before it came to auction and always loved its fantastically sculptural design. It would have originally been completely gilded; for me, it is perfect like this.

2. Wood carving tools set, 19th century

I have collected maybe 300 carving chisels and over 100 moulding planes - these are mostly English 19th century tools which I love to use in a craft that has changed little over time. Making copies of frames in the same way the originals were made is the only way to make them look right. Many of the original shapes have evolved from the making and can only really be understood by the maker.

3. Italian aedicular frame, 15th century. Before and after adaptation to fit Leonardo da Vinci, Virgin of the rocks, The National Gallery, London.

One of my most fortuitous acquisitions for the National Gallery happened purely by chance. Most museums, if they are at all interested in serious framing improvements, rely on the large international dealerships, which not only have many frames to choose from, but also have the sophisticated historical knowledge, which most institutions lack. To enable the National Gallery to do more with the limited funds at our disposal, I have always tried to search for suitable frames at smaller dealerships and auctions. I came by accident across the online catalogue of a general antiques sale at Genoa of over 2000 lots. I looked at candlesticks, chairs, tables etc and stopped in my tracks when I came across three sides of a late 15th century aedicular frame. A type of frame very recognizable from Italian churches, but something I had never seen for sale before. I realized soon that the dimensions were compatible with our version of Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks. The painting was undergoing conservation treatment ahead of a major Leonardo exhibition and it was the perfect opportunity to reframe. We made up the missing parts by looking at surviving frames by craftsmen who worked on the original setting of Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks.

4. Carved oak staircase, Berlin, 17th century

My parents moved just before I was born into a small flat in a very special house in the centre of Berlin. The house is named after the 18th century publisher and Enlightenment figure Friedrich Nicolai who lived there at the end of the 18th century. It is one of a very few 18th century townhouses which have survived in Berlin. When my parents moved in, a number of flats occupied part of the house. The rest contained the regional heritage organization (Institut für Denkmalpflege). This organization expanded and took over more and more of the space for offices until we were the only people living there. Throughout my childhood, we had the little courtyard and all the communal spaces of the house for ourselves at weekends and outside office hours. The house was a heaven and a slice of a different world in the heart of communist East Berlin. My parents still live there and it is still very much a home for me. This carved oak 17th century staircase is one of the grandest features of the building. It took me half my life to realize how special and beautiful it is.

5. Batik silk kimono handcrafted by Maria Schade

My mother introduced her own parents, who were artists in Dresden, to the technique of batik when she came across it at school. My grandparents made traditional tablecloths and wallhangings to supplement their income. In the early 1980s my mother started to batik herself, using white silk to create abstract, almost painting-like designs. She adopted the basic shape of Kimonos as a way of making these wearables. Over time her works have changed and become more and more removed from any traditionally recognizable batik. She creates works of astonishing depth and beauty. Everything is made with an uncompromising eye for detail and years of very slow commercial success have not dampened her creative spirit. Kimonos of her making have hung at the end of my bed for as long as I can remember and are always objects of timeless beauty.

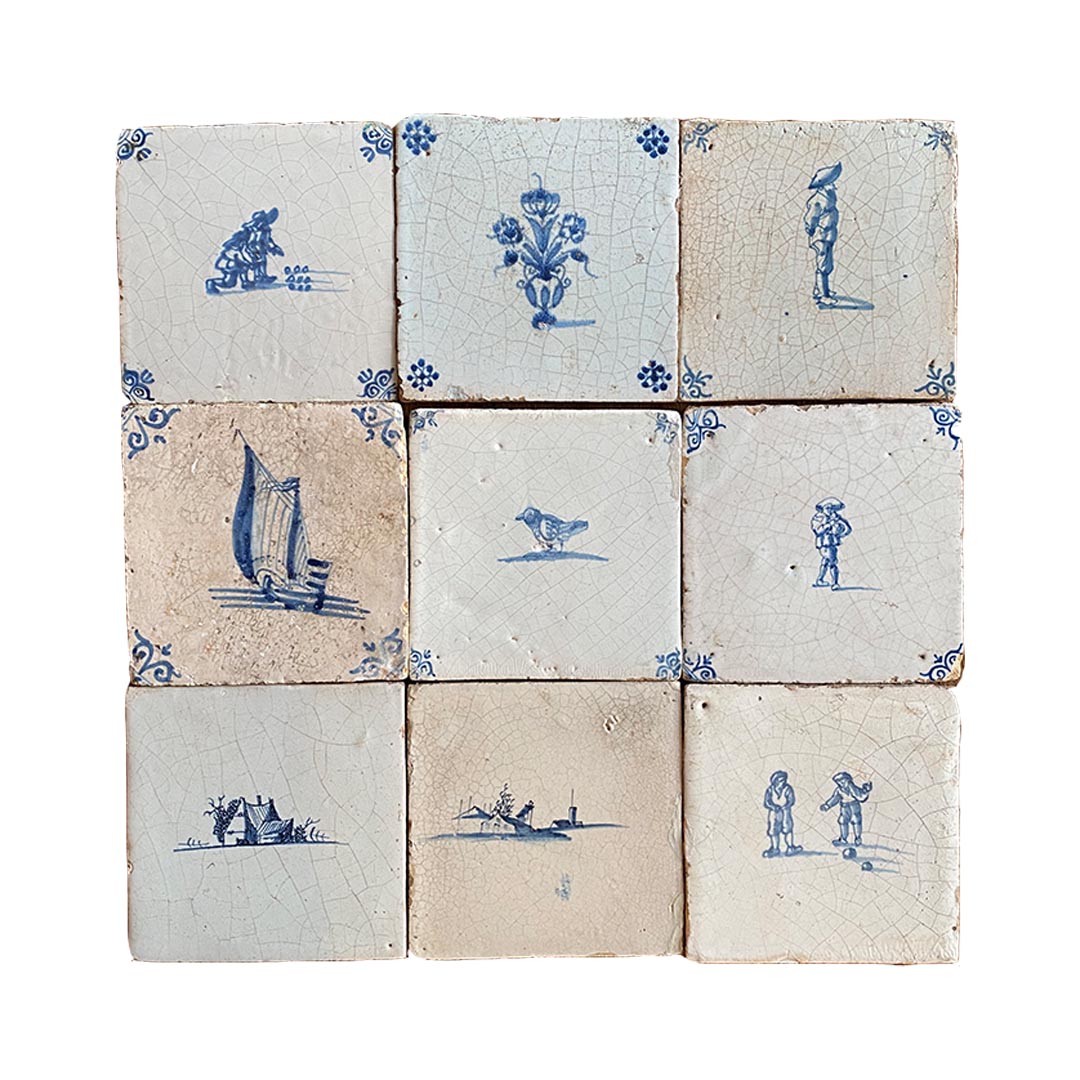

6. Painted Delft tiles, 17th and 18th century

I bought one of these tiles in Amsterdam several years ago and I fell in love with the simple format of these objects that often include a small blue drawing brought to life by a drawn shadow. They are still affordable objects and beautiful things to use in the house. By now I have at home well over 200 tiles decorating various parts of the house. The majority are from the 17th and 18th century.

.png)