Some events more than others, have profoundly determined the destiny of an object and the one of its creator: one of these is a large exhibition staged at the MoMA in New York in May 1972: “Italy. The New Domestic Landscape”. Half a century has passed, but that show remains a crucial moment for Italian design, mentioned in publications and catalog descriptions, to underline that it was a symbolic event of the step forward made by the Made in Italy project in the world. Conceived by Argentinian curator Emilio Ambasz, then curator of the MoMA's Department of Architecture and Design, the exhibition was the first to present to New York (and to the world) the research of Italian design at 360 degrees.

As befits major events, the exhibition came not without controversy: if on the one hand, it marked the strengthening of the export of Italian creativity abroad through businesses and projects, a slice of critics judged it a dispersive and unconvincing operation, even if it is it was precisely in the polycentric nature of the exhibition that its intrinsic value resided, that is the ability to support voices of the Italian creative panorama that are apparently distant from each other, but united by the innovative power at the basis of each individual project.

Paradoxically, New York, a symbol of modernity, gave way to the genius of Italian design at a time when Italy, facing the weaknesses and complexities of the historical moment, was certainly not at the top in terms of avant-garde: but it was precisely the Italian masters' method, their creative process point of view, to conquer New York's sensitivity.

«Italy», stated Ambasz in the presentation of the exhibition, «is not only the dominant force of product design in the world today, but it also illustrates some of the concerns of all industrial societies. Italy has assumed the characteristics of a micro-model where a wide range of possibilities, limitations and criticalities of contemporary designers from all over the world are re-presented through different and sometimes opposite approaches. These include a wide range of conflicting theories about the current state of the design business, its relation to building and urban development, as well as a growing distrust of consumer objects».

Let's get to the heart of the exhibition with concrete examples: organized into two sections, Objects and Environments, the show proposed in the first part about 180 objects including furniture, lamps, accessories and ceramics, created by a hundred Italian designers, selected for their relevance in regard to the "task of design", while in the second, 12 environments were explored — all manufactured in Italy, then shipped to New York! —, articulated on the theme of the house, the "domestic landscape" in its various facets.

It was a certainly ambitious operation from which, according to Ambasz, three attitudes of Italian design emerged: the "conformist" one, a definition that grouped together furnishings that responded to the needs of a traditional domestic life through the innovative use of materials, colors and technologies, among which we recall the Poker Table (1968) by Joe Colombo in laminated wood and steel, or the Soriana lounge chair by Afra and Tobia Scarpa; "reformist" was a section which, aware of the new socio-cultural and aesthetic references, rethought everyday objects through a new narration suspended between art and design and imbued with a touch of irony, as in the case of the woman-shaped armchair Woman (1969) by Gaetano Pesce; "protester" was instead the category including pieces signed by designers who believed that an object could no longer be valid as an isolated entity, but should live in relation to changing social environments and contexts, therefore being flexible and versatile in its function: emblematic of this attitude were for example Tavoletto, a coffee table on wheels with a folding bed inside designed by Alberto Salvati and Ambrogio Tresoldi (1967), or Il Serpentone designed by Cini Boeri (1971), a sofa of unlimited length that can be folded into hollow or convex curves depending on your needs.

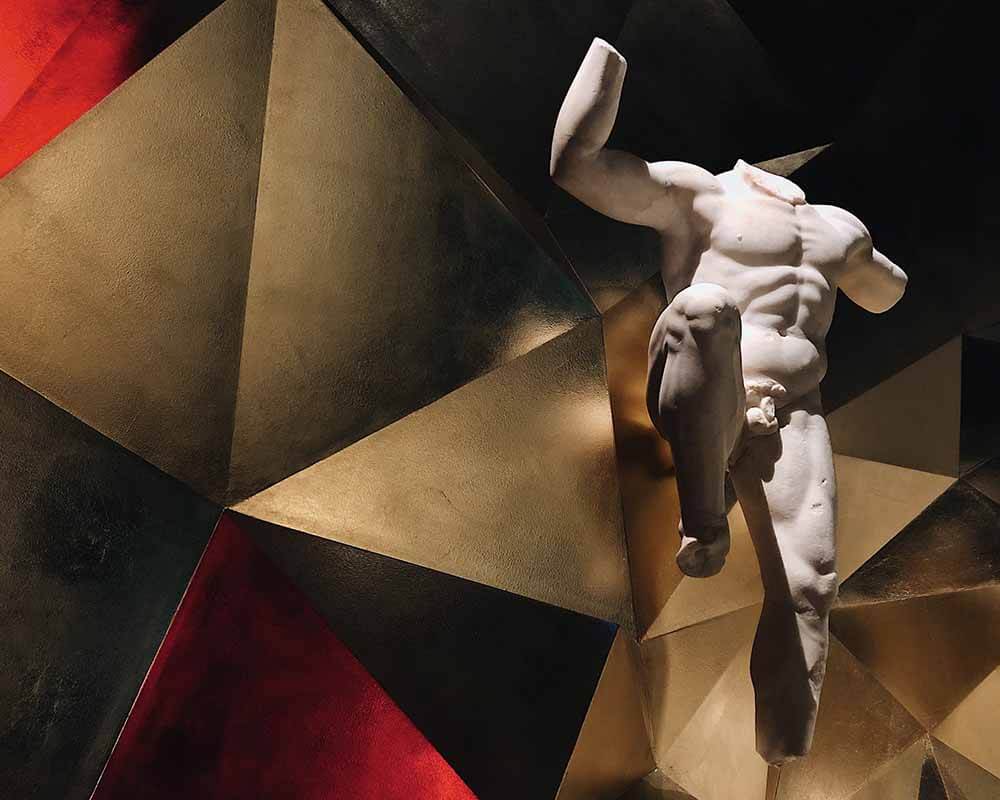

Meanwhile, the Environments turned the spotlight on new models of increasingly informal lifestyles, with a consequent repercussion on the ideal domestic space: Ettore Sottsass exhibited plastic micro-environments on wheels that could be reorganized, while Joe Colombo presented his Total Furnishing Units (1971 /2), fixed plastic units for the bathroom, kitchen, bedroom that can be inserted into any space: a real modular "living structure" with everything needed for living. Multifunctionality was also the common thread of Gae Aulenti's project, a series of molded plastic elements (in the photo), which can be combined to form multipurpose architectural environments.

The catalog of "Italy.The new Domestic Landscape", which in itself represents a beautiful vintage collector's item, is a prestigious publication of 430 pages, in which the projects of the exhibition are reproduced in detail, with brief biographies of the various authors flanked by interventions by leading Italian critics and academics of the time. Discover on intOndo the editions of many objects that were present at the exhibition!

.png)