The story of the mirror may begin with the first time man stood in front of his own reflected image. Probably in prehistoric times, leaning over the edge he discovers that there is someone else looking back at him from the water! Probably an ancestor of the famous Narcissus. The mirror is an element found in the history of art throughout the ages: artists wish to capture deformed reflections, create plays of volume through the various positions of mirrors in a work or prefer to communicate symbolic references linked to the object itself. Venus for one is often depicted in history with a mirror in her hand, a symbol of vanity, femininity, sexuality and life; so ingrained as to become a representation par excellence of woman and the female gender.

It is interesting to note that in numerous paintings Venus looks smugly at the viewer through her reflection in the mirror, in doing so it is possible to see that she is not gazing at herself, as one might assume, but directly engages the audience within the painting. This play of reflections, known precisely as the Venus effect, is one of the many 'illusionistic' phenomena linked to the world of mirrors. An optical trick, if you like, but a highly suggestive one.

There are many cases in which the artist also seeks his own space in his work: mirrors in this respect represent ingenious stratagems. On their surfaces one can often glimpse faces, details of the author precisely in order to make himself part of the scenes and realities portrayed: a sort of 'publicity stunt' so as not to go unnoticed.

One of the artists who succeeds perfectly in rendering reality projected in a convex mirror is Jan Van Eyck, in his Portrait of the Arnolfini couple of 1434: the merchant couple protagonist of the painting, in fact, is not alone in the room. Thanks to the ingenious expedient of the mirror behind them, we discover the presence of the painter himself, who in fact signed his name claiming to have 'been there'. This stratagem involves the observer in the event taking place, through an illusory but entirely verisimilar fiction.

In the large 1656 painting Las Meninas, the protagonists seem to be the young maidens, but in the composition we also see the painter with brush and palette. Velazquez seems to be looking towards us. Thanks to the mirror, however, we discover that there are two characters on the other side of the canvas that the painter is portraying. They are the royal couple Philip IV and his wife Marianne; their daughter, the infanta Marguerite, stands in front of them, in the centre, and attracts attention by her rich dress.

In 1882, in the painting The Bar of the Folies Bergère, Manet chose to depict a typically Parisian setting: a café chantant, a bar where people performed dances, songs and shows. None of these elements, however, appear in the foreground. They are all minutely portrayed in the mirror behind the real protagonist of the work: a common, melancholic waitress, totally estranged from the chaos of the café.

Have you ever noticed that in the self-portraits the pose adopted by the artists is always the same? This is certainly not by chance: it is due to the posture held during the creation of the work. In fact, in order to capture the details of his own face, the painter held the paintbrush in one hand and a mirror in the other. The result is a three-quarter view of the observer.

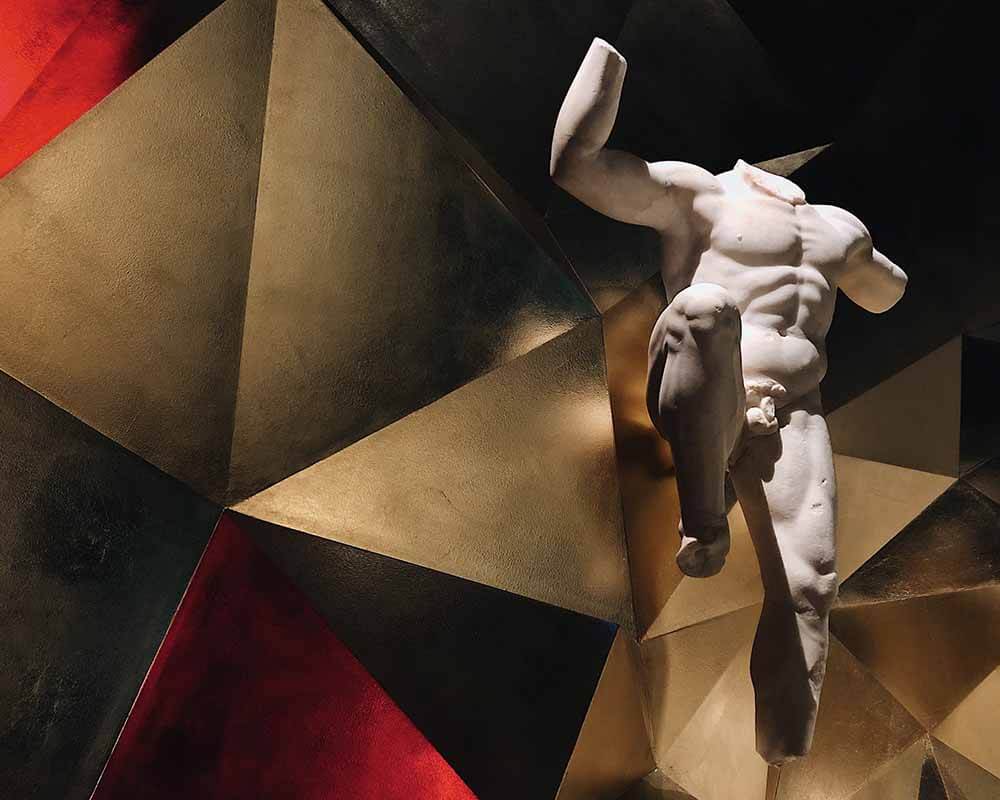

If in the past the mirror has always been synonymous with a faithful representation of the truth and the real shape of the world around us, taking a leap forward in the first decades of the 20th century, it was the Surrealism movement that shattered all certainties. In 1937, Magritte painted The Forbidden Reproduction, a contradiction that created quite a bit of discussion: the artist depicts a man with his back turned in a dark jacket standing rigidly in front of a mirror; in this case, however, the reflection does not show his face, but reproduces his back again. The only difference is that the reflected figure is slightly smaller. The mirror is placed on a marble shelf where a book, specifically The Adventures of Gordon Pym by Edgar Allan Poe, is resting and is correctly reflected. Reality is partly depicted accurately, for example we notice the care taken in painting the reflections in the hair or the veins in the marble, but at the same time there is something surreal, absurd: a reflection that cannot exist in reality demonstrating how the image of reality is not always true.

The same interplay of identification and alteration is also widely used in photography, where mirrors are often exploited in theatre sets and for commercial purposes, as well as in museum and cultural displays to propose, in studied ways, different perceptions of individual works of art in order to make the best of different details or perspectives.

Many contemporary artists have ventured into the theme of reflection sometimes in a social and collective key. Think of Michelangelo Pistoletto and the Quadri Specchianti or Anish Kapoor or Giuseppe Penone. It is precisely the latter in his work Rovesciare i propri occhi (Turning Over One's Eyes) that reflects on the dynamics of the dilation of space and interiority: Penone decides to wear lenses that make him blind while the viewer sees in them the reflection of the space surrounding the artist.

Thanks to their mysterious, almost magical appeal, mirrors are also widely used objects in our private homes: they provide us with a wider perception of space if wisely positioned, they increase the diffusion of light and last but not least, they reassure us that we look tidy before leaving the house.

.png)