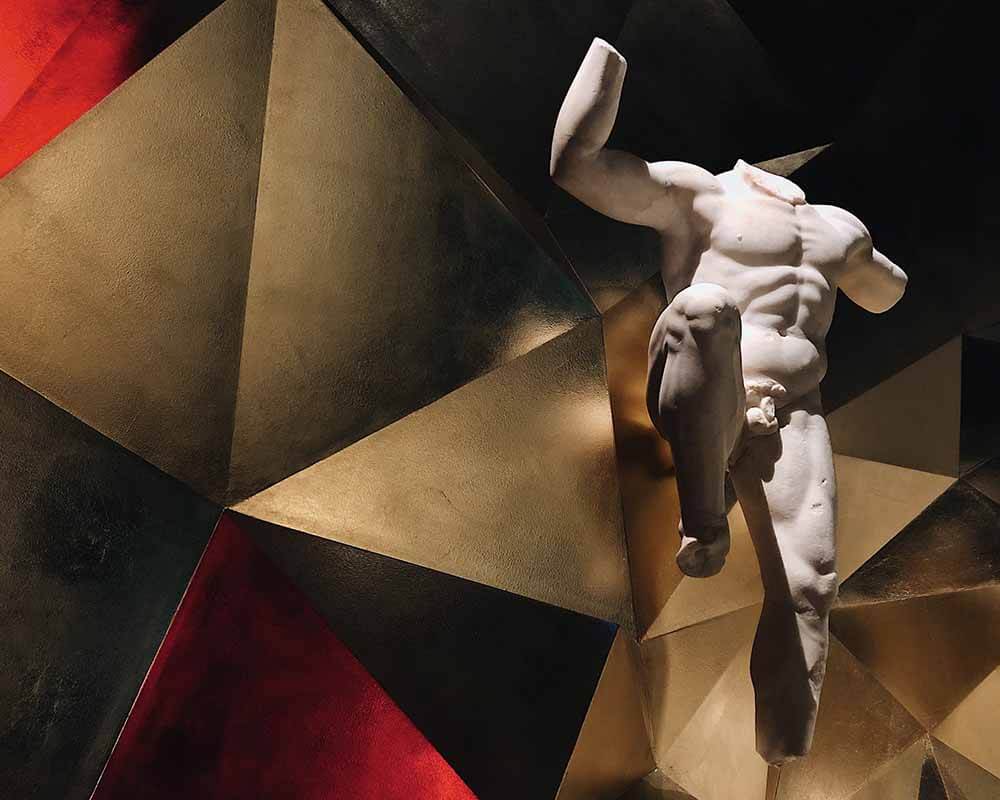

If you think that unicorns, mermaids, taxidermy and rare collections of shells and butterflies are just a fashion of our time, you are wrong. Far from being a modern invention, they have been the core of Wunderkammers in royal palaces, churches and aristocratic residences since the Renaissance. Today, between an exotic-themed party, an animalier runaway and a dip into a pool full of rainbow-colored unicorns, intOndo wishes to emphasize the most intrinsic value of these wonders.

After their appearance in medieval courts and in the early Renaissance, Wunderkammers multiplied in the 17th and 18th century under the impetus of renewed interest in scientific research and on the wave Baroque cult for wonder. Enriched with corals, minerals, advanced scientific instruments and new treasures found by explorers during their exotic research campaigns, they became the archetypes of modern museums, attracting scholars from all over the world. In the 19th century, artist's ateliers became the new cabinet of curiosities. Set up according to an apparent confusion, they transmitted a sense of horror vacui, but were nothing more an expression of their new social status: they served as a tool to testify the artist eruditism. Finally, in the 20th century, the flexible and private nature of Wunderkammers became the expression of a new vision of the world: between art and nature, reality and imagination, politics and religion.

To get a taste of a cabinet of wonders, just visit the former Collegio Romano in Rome - now home to the Liceo Visconti - where a slice of what was perhaps the first museum in the world still survives: the "Kircherian Museum". Although only partially reconstructed, this collection of curiosities put together by the Jesuit archaeologist Athanasius Kircher (1602 - 1680) includes heterogeneous elements ranging from ethnology to physics, from zoology to esotericism, from mineralogy to botany. In fact, it originally reflected what Samuel Van Quiccheberg had included in his guide to collecting in 1565, the book Inscriptionens (or The Titles): artificialia, man-made antiquities and artworks; naturalia, plants, animals, and other items from nature; scientifica, scientific instruments; exotica, objects from distant lands; and mirabilia, a bucket term for other marvels that spark wonder for their beauty, rareness or uglyness.

Who knows what is the effect of all these elements on students that see them on display in the windows of the high school today? They were used to educate and amaze entire generations, but what function do they serve today?

Behind every cabinet of curiosity there is actually an act of pure dedication to knowledge: the idea of collecting, preserving and setting up in a specific way an environment close to us. Also at intOndo we have our own place of the wonders, our "Mirabilia" category, created to include all those collectibles that do nothing but remind us of te voracious desire of knowledge that is typical of humanity and that transcends any historical period.

We invite you to visit our Mirabilia category, because today, as then, we all need a Wunderkammer corner to remind us of the secular human tendency towards discovery, travel, human conquest and progress. Quiccheberg in the 16th century spoke of a microcosm of art, science and mysticism and called it the "Theatre of the world".

.png)